You have probably seen this graph:

…or one of the hundreds of re-skinned, color-shifted, artistically “improved” versions floating around the internet.

No matter how fancy the design is, the idea is always the same:

Lots of simple tests at the bottom, complex tests at the top.

Everyone talking about these stages as if it’s common knowledge what they represent. And it should be. In the first semester of computer science you learn these definitions by heart. Until you try to use them…

Why Does This Question Exist Link to heading

In one of our projects we decided to write an actual test strategy - the dream of any software engineer - so we can go to sleep without having to fear everything will blow up in our faces the next day.

So for once we met for a meeting to decide on a shared list of terminologies, so everyone is on the same page when talking about a “functional gray box unit test verification”.

Shouldn’t be that hard, right?

I opened the notes app, dusted off the old powerpoints my software engineering professor created during the time 4:3 screens where still trendy, and was preparing for a copy and paste session. My expectation was, we meet for 10 minutes, agree that we can use these definitions and spend the rest of the time discussing what we shall eat for lunch.

Spoiler: We didn’t talk about lunch.

Within minutes, it was clear no one had the same definition of what a unit is. It sounds trivial, but it was not clear for us where a unit ends, and a component begins, or where to mock and what to stub. We were not able to find a consensus on the word unit.

The remaining 50 minutes devolved into a heated debate about boundaries, granularity, code structure, philosophy, and the nature of existence.

Definitions Link to heading

According to the ISTQB:

According to the ISO definition:

So “a minimal software item” doesn’t really say anything and the ISOs defines a unit as a component which is defined by a unit.

When you look at real-world test environments, the pyramid often ends up flipped upside down. System tests become the primary way teams validate their software, while everything else gets tossed into a directory called “unit tests” because… well, why not?

In practice, the common understanding is:

- unit tests are fast

- unit tests are cheap

- unit tests make the bulk of the test suit

The Two Extremes Link to heading

Testing. Every. Single. Function. Link to heading

When I first started coding, I took “smallest piece of software” literally.

Getter? Test it.

Setter? Test it.

Tiny wrapper function? Absolutely test it.

One-line delegation? Test it twice, just in case.

Refactoring became hell. My tests didn’t validate logic, they validated my code structure. Changing anything resulted in more time spent rewriting tests than actually working on productive code.

My (flawed) solution?

Disable all unit tests to make the CI happy.

It felt like a weight was lifted of my shoulders. Then reality hit when my “performance improvements” turned into a game of whack-a-bug(mole).

“My Entire Software Is The Unit” Link to heading

The opposite extreme: Only test through the public API.

This turns your test suit into something like a Galton Board. Every test turns into a ball - different shapes, angles, velocities - hoping it bounces in the most obscure ways to test that one edge case in the bottom right corner.

It’s fun until you realize you are playing Pachinko with production level bugs.

What Is Our Goal? Link to heading

If you’ve landed on this post by Googling “What is a unit (test)?” — first of all: Yay! My blog post finally appeased the SEO gods. Thanks for clicking and actually reading it. :)

You’re probably here because one of two things happened:

- Your manager told you to “add unit tests,” despite having no idea what a unit actually is

- You genuinely want to improve the quality and reliability of your software

Either way, the mission is the same.

Stop testing software like it’s a Japanese slot machine and start verifying small, meaningful pieces of the system in isolation.

Instead of randomly feeding inputs into the entire application and hoping the right edge case pops out, we want to split the system into manageable, understandable subsets (units) and test those pieces directly and deliberately.

How can we define a component ? Link to heading

When considering a program as nothing more than a giant tree of function calls, we want to be able to draw a square around one part of the tree and confidently say:

“This right here, is a component.”

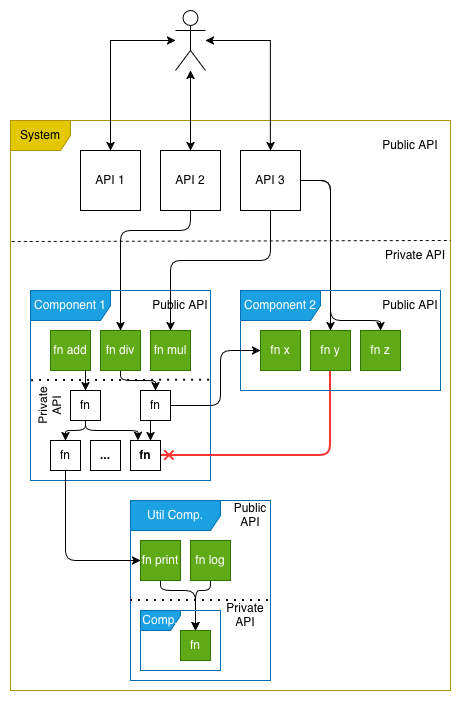

To visualize this, imagine the following generic program structure:

From this perspective, we can describe a component with a few clear rules:

- A system is composed of components. - Each component contributes a distinct piece of functionality to the whole.

- A component exposes a public API and hides a private API. - The public API is how other components interact with it. The private API is strictly internal and must never be accessed from outside.

- The public API must be contract-driven. - Its behavior, inputs, outputs, and error conditions must be explicitly defined and guaranteed, no matter how the internal implementation evolves.

- A component can contain any number of units.

- Components can be made of components. - This allows you to encapsulate complexity without losing structure.

A component is a self-contained part of the system with a clear, contract-driven public API and internal details that remain fully hidden from the outside.

How can we define a unit ? Link to heading

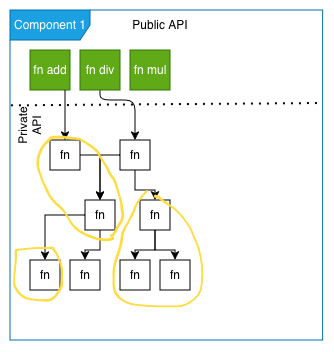

Now that we know what a component looks like, let’s zoom in and examine what a unit actually is:

A unit, highlighted in yellow, is a small, focused piece of logic with limited complexity. Think of it as the smallest part of the system where it still makes sense to talk about behavior.

A unit can be:

- A single function

- A small group of tightly related functions

What matters most is not the size, but the level of complexity. If a function call inside the unit exceeds the allowed complexity threshold, it should be mocked.

But how do we measure complexity?

Yes, there are formulas and metrics that attempt to quantify it. Cyclomatic complexity, nesting depth, lines of code, and so on.

But we want to stay realistic and avoid turning unit testing into a numbers game. Nobody wants to write tests because a metric says “this function is now a 14 instead of a 12.”

In the end, use your head and rely on common sense to decide where to draw the line.